In the early days of Klan organizing, itinerant salesmen known as kleagles roamed the countryside, signing up prospective members at ten dollars each and earning a generous forty percent commission that paid out at the point of sale. These kleagles generated interest in the Klan by stirring up regional resentments at public meetings and organizing local lodges that above all else promised agency for the maintenance of Protestant white supremacy. No less in the North than in the South, millions of men joined.

Much has been written about what a scam the organization was, a marketing scheme that profited a few at the top. Of course, it was other things too: a terroristic hate group, a fraternal society, a Protestant advocacy association, even a political club in places like New York. This has been pointed out since 1921 when the first tell-all exposés began appearing in newspapers. More comprehensive and evidence-driven, Dale Laackman’s recent book Selling Hate: Marketing the Ku Klux Klan shows how the Southern Publicity Association (SPA), a public relations shop with ties to the temperance movement, helped put the fledgling secret society on track to become a jazz-age phenomenon.

Laackman tells the story of how the Klan’s Propagation Department, led by the SPA’s Elizabeth “Bessie” Tyler and Edward Young Clarke, utilized cutting-edge marketing techniques, sending hundreds of kleagles north to grow the organization. Clarke and Tyler divided the country into domains, regional sales territories that were further divided into realms that mostly correspond to individual states. The realms were then broken into districts and further into individual units or chapters. Kleagles were given sales districts and were discouraged from encroaching on another kleagle’s territory.

Evidence in New York shows that territorial boundaries were sometimes selectively enforced by figures higher up the Klan hierarchy. This was tricky in urban areas where prospective members were more likely to be recruited at meetings outside their residential districts. A letter sent to kleagles in New York by King Kleagle Maj. E. D. Smith in early 1924 directs them to not communicate directly with one another, but instead route any correspondence with another kleagle about “organization work” through the realm headquarters in Binghamton. Smith, like every other King Kleagle, had an interest in maintaining orderly control over his sales districts. After receiving six dollars for each new member signed up by kleagles in his realm, the King Kleagle took one dollar for himself then sent the remaining five to Atlanta. There, Clarke and Tyler split the remaining with the Imperial Wizard and the Klan treasury, essentially lining their pockets with money.

The lucrative commissions attracted a certain kind of personality in the tradition of the traveling salesman, a figure with deep roots in the American imagination. While there were kleagles with other motivations, such as radical Protestants or other true believers, as we proceed deeper into the Invisible Empire, we will explore the huckster type of kleagle, the charismatic snake-oil salesman, one of the more salient character types.

Irwin R. Hignett, known in New York as the “Human Dynamo” (and featured on this blog already), was one of these itinerant story-tellers. He likely encountered the Klan on the public lecture circuit while working as a traveling salesman in the period after the war. He excelled at giving speeches and held audiences with great authority. For four years, Hignett honed the skills he would need to sell memberships in an organization that he knew he was not eligible to join. Reports of him often mentioned his verbal prowess as he mixed truth and fiction in stories about his war days, warming up crowds for a magazine sales pitch, or for the American Legion, and eventually for the Ku Klux Klan. But who was this guy, Irwin Hignett?

Hignett was the first publicly-known Klan figure to make a documented appearance in Queens. On December 15, 1923, the night before his speech at First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, Hignett appeared at a meeting of Richmond Hill No. 30, the Friendly Sons of America. When he was introduced in Springfield, the crowd was told he had organized the Klan in Oregon and he said as much in his speech. Whether this was to boost his Klan credentials or for some other reason is unknown, but there was no truth to it. To the crowd, his accent sounded southern; he gave the impression that he was from Louisville, Kentucky, but was not. At the time, Hignett was canvassing Long Island villages like Oceanside and Huntington, giving speeches and generating publicity for the Klan, and with that publicity, memberships. Although his real identity was kept from the public, in meeting minutes from the Richmond Hill Klan, kligrapp Charles Wagner identified Hignett as the man known to Klannish crowds and newspaper audiences as “the Human Dynamo.”

Hignett is not a well known figure, but he is mentioned in a 1953 master’s thesis and in a 2020 book about the Klan. In The Ku Klux Klan in Canada, Allen Bartley reveals that kleagle Hignett was active in the expansion of the Klan in London, Ontario, in early 1923, months before he appeared downstate in New York. Bartley says kleagle Roy Hignett, as he was sometimes known there, had a Canadian military service record and was “readily available to newspapers to tell the Klan story.” And in a three-part series based on an interview with the Toronto Star, he did, to the annoyance of his Klan handlers back in the states. But Hignett’s story—gleaned from old newspapers and public documents—is as remarkable, if not implausible, as the stories he told about himself.

Born May 9, 1894 in Whitworth, Lancashire, England, Irwin Roy Hignett came to the United States on the S.S. Arabic in 1912, settling first in Mansfield, Massachusetts, before his parents arrived and they all made their home in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. It’s not known whether he lied about his citizenship to the Klan but it seems all but assured, given that a basic requirement of membership was a U.S. birth. Online databases show that Hignett did not file naturalization papers until 1926.

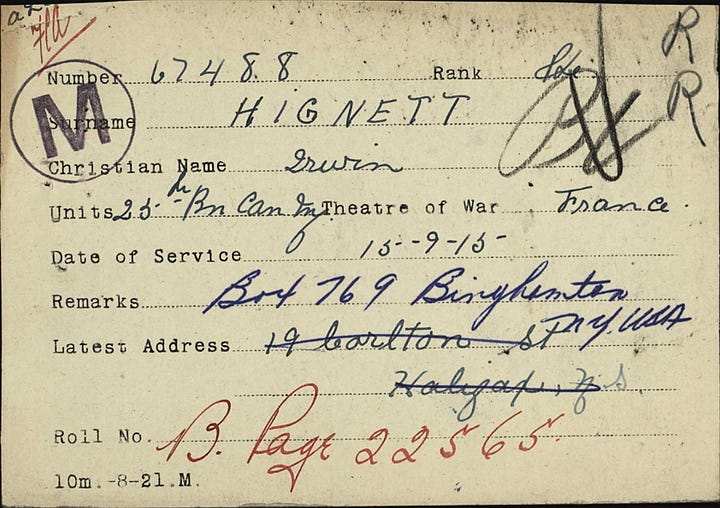

Although he later claimed that he had been more than two years younger and a runaway, in July 1914 he was 20 when he traveled to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. At the time, he was employed by the Lorraine Manufacturing Company, a Pawtucket textile mill, describing himself as a machinist on his enlistment papers. In later tales, he claimed that he dropped out of an unnamed Boston law school to join the fight. Records show Hignett served in the 25th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces, the so-called “Nova Scotia Rifles.”

Commissioned at Halifax in November 1914, the 25th left for England in May the following year before landing at Boulogne in mid-September. That first group would see massive casualties: according to some sources nine of ten were dead, missing or wounded after the first year.

On January 28, 1916, Hignett was on a scouting mission in the trenches near Kemmel, south of Ypres, in Belgium, when he was struck by an exploding rifle grenade. Pieces of shrapnel hit his right elbow and leg and had to be removed; his ulna and tibia were broken. The next day he was admitted to General Hospital No. 26 in Etaples, France, where he stayed until March 9. Surgery performed there removed pieces of shrapnel from infected wounds. He was transferred to the 3rd Northern General Hospital at Sheffield, where more shrapnel and “dead bone” were removed. Not a year later, he would claim to have undergone 17 operations, though a review of his service medical files would suggest that number is an exaggeration. In July, he was sent to King’s Canadian Red Cross at Bushy Park and then Granville Canadian Special Hospital in Ramsgate, Kent, where he began to improve. Although his wounds healed, after his long rehabilitation his elbow would remain in a fixed position, rendering him “unfit for service.”

In November 1916 he eventually found his way to the Military Hospital Commission (known as “B” Unit MHCC) in Halifax, where he worked in the records department while continuing his recovery. No longer able to work as a machinist, his discharge papers and subsequent U.S. immigration documents describe him as a clerk. After an appeal by an examining agent of the pension board, he was granted a modest pension for his disability. On the cover sheet of his Canadian discharge papers are the words “permanently unfit” written in red pen.

In an unusual twist, William and Betsy Hignett in Pawtucket were visited at the end of May 1917 by Lieutenant E. J. Christie, an officer from the Canadian military who informed them that their son had died at the military hospital in Halifax following surgery after wounds suffered at Verdun. The Canadian officer offered to help with having Irwin’s body transported from Halifax to Pawtucket—for a small sum. Heartbroken, the Hignetts arranged for obituaries to be published in local papers, including one in the Boston Globe and a longer one in the Evening Times of Pawtucket.

Relating information provided by the family, the Evening Times said that his body would be transported from Halifax by six non-commissioned Canadian officers under the command of Lieut. Christie. In its story about Hignett’s death, the Evening Times said that because he was one of the “first American boys” to be killed in the conflict, he would be awarded a full military funeral. The story also repeated a claim likely told to Hignett’s parents, that he died from wounds suffered at the Battle of Verdun. The article goes on to say that the ceremonial officers from the 25th Battalion in “full fighting uniform” were all wounded at Verdun. However, it is not possible that Hignett was injured at Verdun: not only did the Battle of Verdun begin after Hignett was wounded and hospitalized at Ypres, the 25th Battalion was never engaged near Verdun, more than 250 kilometers away.

After William Hignett gave the Canadian officer $25 to have Irwin’s body transported from Halifax, he prepared obituaries and made arrangements. But when William wired the hospital for more information, his son wired back that he was still recuperating from his injuries but was otherwise well.

A wire report printed on both sides of the border explained that families were scammed in Fall River, Arlington and as far as Keene, New Hampshire, among other places in New England. A nineteen year-old Canadian war veteran also discharged on medical grounds, Roy C. Morash, was identified as the culprit and arrested. One newspaper story said he received a sentence of four years for the crime, though Canadian immigration documents available online show that Morash returned to Canada the next year. Later ordained a minister, Morash was a self-described bishop of no church in particular. Morash seems to have had trouble with the law in those years and later, even after his ordination. He was arrested in California for sex-related crimes involving underage victims in 1953 and again in Canada in 1969 before his death in 1985.

Before they found out the truth, the Hignett family arranged for a military funeral and purchased a burial plot. There is no burial record for Irwin R. Hignett after his actual death in 1954 in Vancouver, British Columbia, but the FindAGrave website shows a record for a plot for a young Irwin Hignett (1894-1917) at Moshassuck Cemetery in Central Falls, Rhode Island. A note transcribed in one cemetery index suggests the sale was never completed. Whether he rests there, somewhere else, or nowhere, is not known.

The Fates were not done with the Hignett family. Irwin was in Halifax on December 6, 1917, and for a brief time was feared lost in the great explosion, a disaster in the harbor that killed nearly 2000 people and injured many thousands more. He included his experience that day in his talks, having survived mostly unscathed in the incident that saw windows blown out for miles around and nine thousand wounded. A week or so after the explosion Irwin wrote his parents, who shared the letter with the Evening Times.

“Dear Parents Guess you will have received my wire informing you that I am safe. I could have wired right away but after the explosion I was detailed for duty in the hospital rendering first aid.

I had just returned from a very pleasant and interesting trip to Toronto and Montreal. I arrived in Halifax at 1:30 a.m. the morning of Dec 6, and went down to the office to make my report, as I was on special duty for the commission, when about 9 a.m., one of the worst explosions I ever heard took place. I immediately lay flat on my face and our offices were completely wrecked, being right on the water front and only about 600 yards from the point of explosion.

After the debris had finished falling I got to my feet and made my way out of the building, which was a mess of ruins. I was without a scratch. Nearly everyone in there received some very bad cuts and we had two killed in the next office to mine.

My first thought was that a German ship had arrived outside of Halifax and commenced to bombard us, but on getting into the street we were informed that a French munition boat had been rammed by a Belgian relief steamer causing the explosion. I have never witnessed a sight like that we have here. Three parts of the city are just laid flat and Belgium was never to compare with Halifax at the present time.

Every large building that was standing in the south end was used as a hospital and each was filled very quickly. Twenty thousand families were made homeless, with a death rate of over 2500. Believe me, I never want to see the like again.

I received quite a little experience in the hospital. I was stitching up wounds and helping in the operation room. I started in on Thursday morning and had no sleep or rest until Sunday night and we started in some new offices on Monday morning.

It is a miracle how I escaped as I did, and when I saw the condition of the ruins where our offices were it seemed impossible that I could have been inside them.”

In his letter, Irwin Hignett says the MHCC “B” Unit building was 600 yards from the blast. A review of a map of the blast zone shows that the Pier 2 location of MHCC was more than 2000 yards away. Nonetheless, according to Stuart Hunt in Nova Scotia’s Part in the Great War, the MHCC hospital and offices at Pier 2 were leveled. Hunt, like Hignett, compared the scene to what he witnessed in France. After his discharge and return to Pawtucket, in an interview with the Evening Times, Hignett provides more detail of the moment of the explosion:

“I was standing at my desk in government pier No. 2 about to dictate a letter to my stenographer. She was on the opposite side of the typewriter table about to take her place when the detonation rang out.

“Instinctively, I dropped on my face shouting to her at the same time to do the same thing. She was bewildered and stood motionless. Instantly, a noise that sounded like a whiff reverberated through the city. Buildings fell […] crumpled like paper, wood was reduced to splinters and glass was ground as fine as sand.

“My stenographer was cut severely about the face and head by flying glass and debris. The typewriter and table were blown through a partition and into the next room. When all seemed quiet, I pulled myself from beneath the wreckage and found that I was not even scratched and quickly started to assist in the relief work. Out of 40 who worked in my room and several hundred who were engaged in the pier building, only four escaped without a scratch or cut. A sergeant in the lower part of the pier building and a sentry on guard were killed.”

Discharged from the Canadian military, Hignett returned to the United States where American audiences provided many opportunities for him to tell his stories. In March 1918, barely a month after his departure from Halifax, Hignett appears in Elmira, in New York’s Southern Tier, telling stories about life in the trenches. In just a few days, he gave talks at the Rotary Club, at a “thrift stamp party” organized by the Daughters of Isabella, and at a much larger stamp party held at at the post office, an event which drew 5,000 people. Speakers at the post office stamp party included William Hosie, a member of the British Royal Flying Corps who “came from England with a Curtiss aeroplane man of Hammondsport,” Sergeant John Leaman, who fought in the Battle of Ypres and was “wounded by shrapnel and lost all of his teeth through poisoned gas,” and Hignett, who was said to have “fought in the Battle of St. Elio Craters, known as Bloody Craters, also the Battle of Kemmell.” So goes the first of a thousand ways of telling the same story.

Advance publicity for an event in Elmira published in the Star-Gazette reproduced the basics of Hignett’s most desperate hour on the battlefield:

“At Ypres he was on scouting duty, when a bomb thrown at him exploded, wounding him in nine places. Just as he was struggling back through the barbed wire, toward his lines, a German soldier bayonetted him through the arm, as he sought to ward off the blow and he lay 36 hour on the field for dead before he received medical attendance.”

Except for having received shrapnel in his leg and arm, there no evidence that of any of this is true. The Star-Gazette reported that he joined the Nova Scotia Rifles as an American citizen, an idea reaching peak fiction when he encountered the Klan four years later.

There is no further trace of Hignett in Emira in spring 1918, but he does appear back in Pawtucket in June, where he married Florence Laurel Rudd, an Erie, Pennsylvania, native who went by Laurel. While in Pawtucket, Irwin gave a talk at the Woodlawn Baptist Church men’s class featuring stories about trench warfare and his scouting efforts, his injuries and the Halifax explosion. It even included the “air raids in London.” According to the Evening Times, “The local boy has commenced a series of lectures to social and fraternal bodies, his true and accurate accounts being a revelation to hundreds who actually do not understand what fighting in France means.”

If Irwin Hignett gave any further talks in 1918, there is no record of it that can be found in newspaper searches. The next year he turns up with Laurel in Western New York, where he was employed selling magazine subscriptions for a company in Buffalo. Near the end of May, after two weeks working the neighborhoods of Lockport in Niagara County, Irwin Hignett and P. Thompson, his sales associate, appear in an article in the Lockport Union-Sun and Journal thanking the people there “for the kind treatment extended to them while in town in the interest of several Magazines.” The Union-Sun and Journal went on to explain:

“Hignett and Thompson were severely injured in the war in France, so that they are unable to do inside work and for this reason have taken up the magazine subscription business. Mr. Hignett was injured several times in the third Battle of Ypers, and Mr. Thompson lost an eye in the battle of Vimecy Ridge.”

Having only “P. Thompson” to work with, it’s impossible to find anything about him. As far as Hignett, some versions of his story have their roots in his experience, but not this one: the Third Battle of Ypres began fully six months after he had been hospitalized.

The two men set out to further canvass the Niagara frontier, first at Newfane, then at Ransomville, between Lockport and Niagara Falls. We wouldn’t know anything about this except that a bit of trouble in Ransomville was reported in the Niagara Falls Gazette. “No end of excitement was caused here,” the Gazette wrote on July 1, 1919, after several women became suspicious of “two supposedly returned soldiers soliciting magazine subscriptions.” One of the men had lost an eye and the other was “wounded in his arm and leg.” Identified as Thompson and Hignett, both men were wearing army uniforms and carried papers signed by the secretary of the chamber of commerce and the “head of a local newspaper” in Lockport, just a few miles away. Thompson and Hignett were compelling and sympathetic figures who used their stories to generate sales of magazines, but one man who remembered their visit in May ordered a magazine for boys and never received it. Enough people were concerned that a group of women approached Thompson and Hignett at an ice cream parlor and demanded their money, calling them out. Insisting on their good intentions, the men asked the women to call them in Lockport so as to “satisfy themselves” and suggested they might regret making a “hasty” decision. It is not clear what they repaid, but as the Gazette put it, “others who gave orders to the men are now awaiting the receipt of magazines which will clear the men of suspicion.”

Apparently, they were not cleared. The next week, the Gazette ran a follow-up story, reporting that the Rev. H. E. Hinkley had suspicions about the salesmen’s offer of three dollars for nine dollars worth of magazines and contacted the magazine subscription business in Buffalo, the Allard-Brophy-Timmons Company, “regarding the honesty” of the two men. It turns out that the price of three dollars quoted was the commission the men would earn on the sale; customers would be required to pay the remaining six. The Ransomville customers were unaware of this because the salesmen used blank payment forms, which they marked as paid in full, and not the company’s receipts. According to the Gazette, the two men “stated the fact that they were wounded soldiers accounted for the unusual low prices offered.” As summer ended, patience dissolved. In September, the Lockport Union-Sun and Journal ran an ad for several days offering a reward for the whereabouts of the two men who had disappeared from the area.

Census records tell us that in 1920 Irwin and Laurel Hignett lived at 2583 Main Street in Buffalo. In October of the year before, at an organizing meeting of more than 100 Buffalo residents, Hignett was elected secretary-treasurer of a branch of the Returned Soldiers’ Association composed of Buffalonians who served in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. An article in the Buffalo News indicated one motivation for creating the advocacy group: at a large mass meeting to be held a few nights later the “gratuities given to Canadian citizens for military service and denied to American members of the C. E. F. will be discussed.”

In March 1920, newspapers in Cattaraugus County reported that Hignett, a “Buffalo magazine salesman,” was arrested in Olean on charges of grand larceny in the second degree. Based on information from a warrant in Buffalo, he was taken into custody at the Olean House by the local police chief who drove him to Buffalo to answer the charges. The nature of the charges were not reported in the newspaper. Insisting it was all a misunderstanding, Hignett returned immediately and visited the police (and the newspaper) to tell them he had been cleared and no longer faced any charges. The Evening Times of Olean included his explanation: “I showed them that I was all right,” he said. “I am selling magazines in this city, and I didn’t want any of my customers to fear that they were going to lose money entrusted to me, so I lost no time in returning.” The Evening Herald in Olean gave a bit more insight into his sales practice:

“Hignett has been soliciting the grammar schools here, where he has been talking to the school children about his experiences overseas and has been getting subscriptions to magazines. Considerable anxiety was expressed by a number of teachers in the public schools, when they learned of the agent’s arrest. Local police authorities said today that Hignett is “on the square” and will be allowed to continue his soliciting.”

In 1921 Hignett showed up in Zanesville, Ohio, selling magazines as a representative of the International Sales Co. of Chicago. Identical stories in the Zanesville Signal and the Times Recorder show activity similar to reports from Niagara County. “War Veterans Sell Magazines Here,” said the headline in the Recorder. Accompanied by a veteran from Chicago and endorsed by the local American Legion post, Hignett was described in the local paper as a veteran from Providence with vocational training from the government “earning money in this manner to enter Law school at Ann Arbor” so “any courtesies shown him will be very much appreciated by the parties concerned.” In this version, his service began in 1915 and continued until the Americans arrived and he transferred to the First Division. He was said to have been wounded nine times and been gassed. His wounded arm was described as paralyzed, and there is reason to believe that much is true, or mostly true. The next month a short article in Zanesville papers said he broke that arm trying to board a streetcar.

As Hignett moved west across Ohio, his story continued to move also. He also began to deepen his ties to the American Legion, which became a venue for his “lectures” as much as an endorser of his sales work. In advanced publicity for his appearances in Tippecanoe City and Troy in January 1922, Hignett, now known as Sergeant Hignett, claimed that he fought for both the Canadian and the American armies and that he was “working his way through” law school at the University of Michigan. The Troy Daily News suggested that his appearances in conjunction with a Legion drive led to fifty new members in a week. “This man was in a number of engagements,” the Daily News wrote, “was wounded nine times and captured by the Germans and he is said to be a very interesting talker.”

In February 1922, Hignett addressed school children in Dayton and reports written by students appeared in the Dayton Herald. First, from the E. J. Brown School report by Evelyn Lytle and Florence Nielson, student reporters:

“Irwin Hignett, a World war veteran addressed the school Thursday morning. He related many interesting and thrilling experiences which he encountered at the front. He is of a family of six children. Three of which were killed in action and two, including himself, were permanently wounded. He had 27 operations as the result of nine very serious injuries—wounded in several places in the right arm, a bayonet wound in the stomach, a silver plate was necessary in the leg. Also, he was severely gassed. He was in the enemy’s prison for seven months. Some of the things he saw were so terrible that they will never fade from his memory.”

The report from the Weaver School two weeks later includes some details first reported by Weaver students Merlin Test and George Lohnes:

“Mr. Hignett, an ex-soldier, spoke to the fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth grades Thursday. Although of Scotch descent, Mr. Hignett is an American. His early education, he says, was obtained in Glassgow, Scotland. When seventeen years old he ran away and joined the Canadian army and went to France in 1914. He fought until three months before the armistice was signed.

“He was dressed in his Scotch costume and the children were delighted. He told of his experiences in France, which was appreciated very much and the children are wishing for his return.”

The next month, in appearances at the the Arabic Club in Dayton and the Dayton Real Estate Board, Hignett told all about his about his experiences fighting with the Canadian Black Watch “Ladies from Hell.” Obviously, he was not a soldier in that infamous unit, but it’s understandable that he wished he had been. Both of his brothers served in that unit during the war. Perhaps because of his affiliation with a Chicago sales firm, the Dayton papers describe him as from that city also.

This is a good time to note that we have no firm date as to when Irwin R. Hignett began his association with the Klan. One thing is for certain: the story that he must tell to be a member of the American Legion is related to the story he must tell to be a member of the Ku Klux Klan. If he must be a veteran of the United States military to be a member of the American Legion, then he is a member of the First Division. If he must be an American-born citizen to join the Klan, then he was born in the United States.

Another thing to know is that in 1922 as Hignett migrated west from Dayton into Indiana the Klan was also on the move there. At some point, Hignett crossed paths with them. He would have had many opportunities.

Leonard Moore, in his book Citizen Klansman reports that the Klan appeared in Evansville in fall 1920, the first klavern north of the Ohio river. Joe Huffington, a native Texan and associate of Hiram Evans, was the first of the kleagles who would organize the state from his base in Evansville. Growth remained slow until early 1922. Inadvertently hyping the Klan, newspapers announced the first church visits in Evansville in March 1922. Large rallies, parades and the strong organizing staff provided by the Klan’s Propagation Department soon followed, allowing kleagles to launch units in nearly every town and city in the state, growth that would soon make Indiana the most populous realm in the Invisible Empire. Over the next months, from Evansville in the south to South Bend in the north, the Klan staged public lectures and dramatic initiations with fiery crosses.

It was at this time that the notorious David Curtis Stephenson joined Evansville No. 1 and began his rise to power. By late summer, “Steve,” or “the old man,” as he was known, was King Kleagle of Indiana and Ohio, becoming Grand Goblin when they were chartered the next year. Through arrangements with Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans, Steve ruled the entire northern United States. His subsequent fall after his conviction for the rape and murder of Marge Oberholtzer in 1925 is documented in many books, including Moore’s.

During the first months of 1922, before Stephenson was a factor, other Klan organizers arrived in the Hoosier state. Some of these figures appear in New York just months after their time in Indiana. Correspondence between Atlanta and Maj. E. D. Smith, future King Kleagle of New York, shows that he was active in Indiana in the later part of January and at least through February. Hailing from Gulfport, Mississippi, Smith made Indianapolis his base in the state, living out of a hotel and utilizing a post office box as an address. It’s not clear what his role or title was exactly, but he was certainly more than a simple kleagle.

In 1920, the then-Captain Smith was a founding organizer of a volunteer militia, a company in Biloxi that became part of the Mississippi National Guard. Perhaps to hide his association with the Klan, Smith told the Sun Herald in January 1922 that he was headed to Chicago, rather than Indiana. Then in July he said he was home for a visit before taking up a position as a military trainer in New York. There, he was a trainer of sorts: as King Kleagle he would oversee the development of a large state organization, one that included paramilitary Klan units the Empire State Rangers, the Nassau Rangers and the Klavaliers, who claimed hundreds of members in Queens alone.

In Indiana, E. D. Smith worked to build up the Klan by staging public meetings and demonstrations. He also arranged for Klan-approved speakers to appear at private meetings for which there is no record, paying the speaker’s fees and transportation. On behalf of the Klan he made use of all the accoutrements of a regional sales manager: employing a stenographer, renting an office and all its effects, sending expense reports to E. Y. Clarke for approval and reimbursement. The expense reports held by University of Alabama show that Smith was involved in organizing speakers at meetings or events in the towns outside Indianapolis, including Muncie, Edinburgh, Fortville, Sheridan, Noblesville and Lebanon. None of these events were recorded in the newspapers. He also expensed visits to Hammond, Gary, South Bend and Ft. Wayne in the north. In addition to his room, office, and so forth, each week’s report included dinners with local Klansmen, ministers, business leaders and public officials, including a judge. He also referred to needing to advance kleagle Paul Gordon some funds to cover an expense. In a note appended to the expenses for the week ending February 25, Smith reports eleven new members, a “slight increase” but an overall total of 162 for his time in Indianapolis. A slight increase indeed, when compared to the four digit numbers produced weekly by Indiana kleagles over the next year.

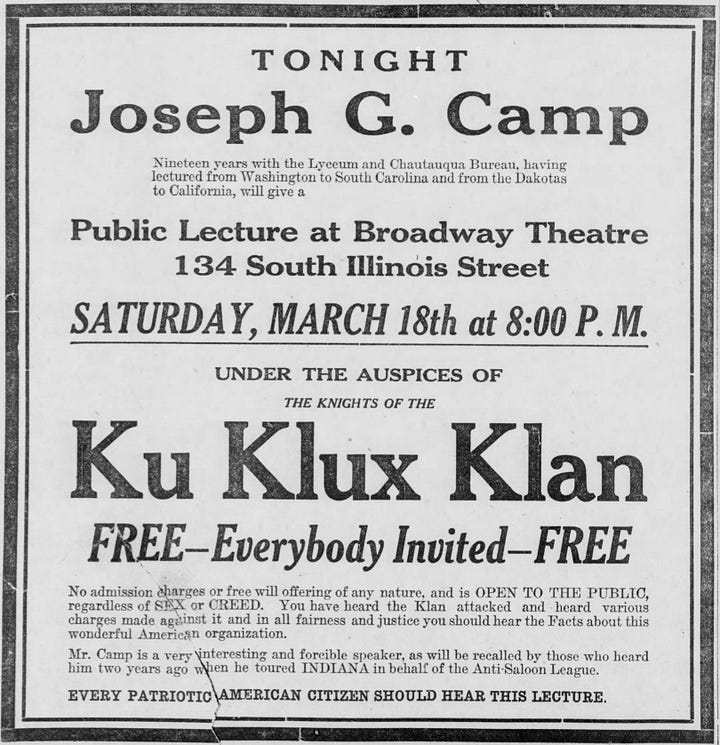

While Emmitt D. Smith mostly avoided public scrutiny in Indiana, in March 1922 his request for use of a public building in Indianapolis was denied. After some back and forth, he resolved to find a space that was not publicly owned. He secured the Broadway Theatre for the March 18 event featuring Joseph G. Camp, a renowned lecturer with two decades of experience on the Chautauqua and Lyceum circuits. There is some question as to whether the meeting actually happened. Despite advertisements for Camp’s “free to all” talk about the Klan, other newspaper accounts suggest Smith’s effort to secure the Broadway theater fell though.

Camp, who was said to be with William Simmons on Stone Mountain on that night in 1916 when the modern Klan was born, was known as the “Orator of the South,” which also happened to be the title of one his talks. Another popular talk was “Truth and Shams,” but like the others it is lost to history. The frequent Klan lecturer died suddenly that summer at his home in Georgia. Obituaries politely described his association with the Anti-Saloon League and made no mention of his work for the Klan.

Presiding over the funeral of Joseph Camp was the Rev. Caleb Ridley, another Georgian from the Klan’s earliest days. Considered a “pioneer member” of the Klan if not a co-founder, Ridley traveled widely to give talks as the Imperial Kludd, the national chaplain. Returning time and again to Indiana, Ridley was a speaker at demonstrations planned by the Evansville klavern in multiple cities, including Terre Haute and Indianapolis. A more significant figure than the paucity of scholarship would suggest, the Caleb Ridley rabbit hole remains open for all explorers.

With Ridley at some of these events in Indiana in 1922 was the Rev. Dr. Charles Lewis Fowler, a former college president and Baptist minister. Fowler was most often introduced to audiences as the founder of Lanier University, a 100% American university that sought to teach southern values but struggled financially until the Klan took it over. Before that, Fowler was president of Cox College in College Park, Georgia, his second such appointment. Although it is not known if they knew each other, before Fowler was named president of Cox in 1914, the dean there was Dr. Lester A. Brown, another minister/educator who in the 20s served as a national lecturer for the Klan, including in Indiana and New York.

Educated men like Camp, Fowler and Brown were professional orators, and their skilled apology for white supremacy and 100% American values must have been eye-opening to northerners unfamiliar with the modern Klan. When Brown spoke that September in Tipton, not far from Anderson and Indianapolis, the Daily Tribune remarked that the orderly scene defied expectations and that “the speaker was not that rabid species so often true of the itinerant street orator.”

If E. D. Smith is not well known to scholars, remembered mostly as the King Kleagle of New York or as the namesake of the Emmitt D. Smith Klan No. 38 of Jamaica, then the opposite is true for Fowler, a more prominent figure remembered in much greater detail. This blog will certainly get to Fowler soon enough, for he too moved to New York, where he launched the American Standard newspaper.

By summer, Smith had moved on, first home to Gulfport, then to Buffalo and eventually Binghamton, where New York’s combative new King Kleagle setup the Klan’s state office. As Smith was leaving, Fowler arrived from Atlanta for a series of lectures on behalf of the Klan, some of which were promoted with large ads in Indiana newspapers and by all accounts were attended by as many as 5,000 people. For context, a year later many times that attended a huge rally in Kokomo. Later in the summer, Fowler continued north into Wisconsin for more Klan lectures—and publicity. He returned to Atlanta for a brief period before taking off again for New York, lecturing in Rochester and Olean in the west and on Long Island in the east.

Other than few names, like Huffington, Gordon and Hignett, most of the kleagles who organized Indiana are unknown; Within a couple of years, the state would have somewhere between 160,000 and 240,000 members, half a million if you follow the Klan’s numbers. Richmond, Columbus, Muncie, and Anderson, these are just some of the Indiana towns where the Klan was active and where Hignett operated under the auspices of the American Legion, giving speeches about his time in the war and “selling magazines.”

Other than the brief descriptions given in the papers, there is little known about these events. It’s possible that they were Klan events, organized under the cover of the American Legion. What’s more likely is that Klan organizers parasitized Legion events, operating in what would have been a generally friendly environment, much like how Oscar Haywood was said to have distributed Klan literature in the pews at Manhattan’s Calvary Baptist Church.

The Klan’s relationship with the American Legion varied regionally and even from post to post. While the Legion was officially opposed to the Klan, the Klan recruited among its members and generally ran on a parallel track as the American Legion in the early 20s. In New York City, some posts of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars had Klan members among their ranks and this generated conflict. The large numbers of Legion members in the midwest who were also Klan members may have made Klan recruiting at Legion events less of an issue in Indiana than elsewhere. The American Legion’s struggle with the Klan issue, as well as accusations of vigilantism and right wing sympathies of some of its members, deserve another look. It’s certainly possible that Hignett’s appearances in front of American Legion crowds, or at events they sponsored, were covers for Klan activity, but there is no proof of that. From reports at the time and later, we know Hignett traveled around central Indiana giving talks during the same period as a massive surge in Klan organizing and growth in the same area.

In Monticello, north of Indianapolis, news of a kleagle’s arrival in town appeared in the Monticello Journal. “A traveling representative of a secret organization, generally supposed to be the Ku Klux Klan, has been active in this community during the past several weeks attempting to interest local men in taking out membership in the society,” the paper wrote. The article mostly described the membership application and basic tenets of the organization, adding that the visiting salesman “is said to be of French descent and speaks with a slight accent.” This may be a reference to the well-traveled Hignett, but it is impossible to say. Surely a Klansman with anything other than a southern accent would have been very notable.

Although we know he had been active in the second half of 1922, there is no mention of Hignett in relation to the Klan in Indiana newspapers until 1923. Moore, in his account of the growth of the Indiana Klan, estimates that Klan organizing in the state really took off in the summer of 1922. E. D. Smith reported 162 new memberships in February, but by fall the weekly recruitment numbers averaged about two thousand per week.

In August, when he was likely at his most active as a Klan organizer, Hignett gave a series of talks at the Rotary club, Kiwanis, and other fraternal organizations, even the engineering club of the Remy Electric company in Anderson. In publicity for an appearance before the American Legion there in August 1922, ambiguously characterized as from “Hamilton, O.,” Sergeant Hignett is cast as one of the surviving members of the “original Black Watch Canadian Regiment” that was “almost annihilated by the Germans.” A picture of him in the Anderson Herald showed him in uniform, holding a rifle and wearing the traditional kilts, even though he was never a member of that unit. In the photo, his right arm hangs awkwardly to his side.

The report of Hignett’s speech at an American Legion event in August at the Crystal Theater in Anderson shows his life story reaching new heights of fabulation. It contains a mix of Klan eligibility requirements and patriotic credentials. According to the Times-Tribune summary, he was “born in Massachusetts and raised in Pawtucket,” and “after graduating from high school, he ran away from home just at the beginning of the great world war. He was 17 years old then.”

“After six weeks’ training his outfit was sent overseas and was the object of the first poisonous gas attack by the Germans. Gas masks and other means of combating gas were unknown at that time, and as a result, this outfit lost 60 per cent. of its men in the first attack. The scene, as described by the sergeant was too horrible for human eyes. He himself lost the roof of his mouth.

“In 1917, when the United States entered the war, Sergeant Hignett joined the 16th Infantry as a scout. He was later captured and placed in Friedburg prison, where he was held until the signing of the armistice.”

The story in the Times-Tribune of Alexandria also included how he was wounded nine times. Hearing about it all was entertaining and the people of central Indiana could not get enough. “He is a good speaker,” the article said, noting that he already signed on for a Legion picnic the following Sunday where he would tell more details about what he experienced. “He will appear in Kilts, the uniform of his outfit.”

The American Legion picnic was held at Vinson’s Grove, adjacent to an old I.O.O.F cemetery, about a mile south of Summitville and a popular location for picnics and patriotic observances. Participating families who pre-registered at a local pharmacy were provided transportation out to the grove. There, organizers from the Alexander Bright Post of the American Legion in Alexandria and its auxiliary gave out French money, which could then be exchanged for ice cream and other treats. The program for the event was published in the paper and included Hignett’s presentation, one by an officer of the Legion, but also pie eating contests, baseball, an orchestra concert, vaudeville sketches, and more. Significantly, the opening prayer was given by the Rev. Henry H. Wagner. Over the next two years, Wagner emerged as one of many unapologetic pro-Klan clergy in the state of Indiana.

That fall, Hignett spoke at the First M. E. church in Anderson, and although we do not know in this case whether this was a Klan speech, Protestant churches were a reliable target of Klan recruiters. In September, 300 attended a “men only” speaking engagement organized by the American Legion post at the Family Theater in Alexandria, fifty miles northeast of Indianapolis. At the meeting Hignett acknowledged that he was not paid for his speeches, but was “interested in the sale of a magazine, for which he will solicit subscriptions in this city next week.” Another event at the Lions Club in Anderson followed in October. Less than a month later, he appeared at a Lions Club “Ladies Night” at the Chamber of Commerce in Muncie. The night promised dinner, a talk on “Americanization” by Hignett as well as other performances and dancing. Hignett was described as “an ex-Canadian soldier who transferred to the American army when the United States entered the war.” Of course, much of it was untrue. What is likely true is that he spoke on Americanization at the women-only event. Some of these events are suspicious: the topic of Americanization, for example, while broadly popular was of particular interest to the Klan and allied Protestants.

Irwin Hignett’s busy public schedule disappears from the newspapers in November. On Armistice Day, he missed an appearance as a featured speaker at the high school in Alexandria. There is no mention of him until the last day in February, 1923, nearly four months later, when Hignett is described as the “presiding officer” at a Ku Klux Klan initiation ceremony at First Christian Church in Alexandria.

For the interim period we have few clues as to what Irwin Hignett was doing, but the Klan was very busy in the towns surrounding Indianapolis. Newspapers in the area covering public Klan meetings in or near Tipton in October 1922 suggest that Elwood, Muncie, Kokomo and Anderson had already been organized into units. Elwood native Merrill Jones’ 1953 thesis provides a brief history of the Elwood unit, known as White City Klan No. 19, for which Hignett was the kleagle. Because uncharted or provisional units typically would have had the local kleagle as a presiding officer until such time as their charter required them to elect an Exalted Cyclops, Hignett would have presided over meetings in Elwood, and presumably other nearby towns as well.

A meeting was held in Tipton at the Woodmen Hall on Monday, October 16, by invitation only. The Call-Leader of Elwood said that the “best citizens” were invited, a top-down strategy designed to change the perception of the Klan. Names of potential members were brought forward. Palm cards containing a few messages and some meeting info or a PO box were distributed widely. Apparently, this worked in Tipton. The paper claimed that “a large number who have either been recommended as desirable candidates or who have themselves expressed a willingness to become members were present.” The meeting was addressed by someone from the organization who was not identified in the paper other than that he came “from a distance.”

A preview of the invitation-only meeting in Tipton, sent by the “Kleagle of Tipton Klan” to the newspapers with a request that it be published:

“There will be a special konklave of this organization, open only to those who have received invitations, sometime during the present week.

“The purpose of this meeting is to discourage the present thought of radicalism that is held by a few of our good citizens.

“This organization stands for ‘the betterment of mankind’ and the ‘happiness of humanity.’ Its motives are unselfish and its impulses noble.

“The membership is open to men of good character, who agree with each other on religious principles, law and order. It is necessary that a man be native born, that he comes well recommended, and of white parentage. He must be a patriotic supporter of the constitution of the United States of America, subscribe to its constitution and laws and willingly ready to honor its flag above all others. His pursuits in business must be legitimate, his word and honor unquestionable and his reputation clean.

“There is a place for such a man in our organization. Our associations together will be of benefit to him and this community.“If the high type of citizenship that already represents this organization in your city, who are bound together by Christian Protestant impulses to develop character, protect the chastity of womanhood and exemplify a pure patriotism toward our glorious country; who look upon the fiery cross as emblematic of the Christ who died for mankind and His blood which was spilled to redeem the world; if such men can harbor and practice radical motives, then our organization can be said to stand for radicalism.”

To further this effort, copies of The Fiery Cross newspaper were distributed to Tipton residents. The Fiery Cross would become the organ of the Stephenson regime in Indianapolis but October 1922 is fairly early in the history of that paper. Local papers speculated in competing accounts as to where the Klan agents organizing Tipton were coming from, suggesting alternately Kokomo or Elwood and Anderson. The Daily Tribune in Tipton also published the letter, but also provide some context, interpreting the signature as meaning that there was already some Klan presence in town:

“It is said that several Tipton people were inducted into the organization in other cities last spring and that meetings were later held in Tipton, but that enthusiasm dropped somewhat until were started again. A speaker appeared on the public square a few weeks ago and outside workers have since appeared here to stir things up it is said. Lately, within the past few days, it has been known that the Klan had a representative in Tipton and rumors were numerous that activities were about to start. This letter confirms this and if rumors can be relied upon this meeting will be followed by other activities.”

“Other activities” surely did follow and Tipton Klan No. 40 was eventually received a charter from Atlanta. The Daily Tribune also recognized that Indiana was “strongly organized by the Klan,” claiming that “it is said that this state is the strongest Klan state in the north.” Making no mention of Indianapolis, the paper noted that Kokomo, Frankfort, Crawdforsville, Newcastle, Muncie and Anderson all each had thousands of members each. A week later, 125 more were initiated at Anderson after a parade of 300 klansmen and a Klan band (all in robes and masks).

The first signs that the Klan had come to Elwood were in early October when a notice that there was going to be a “big klan meeting” at Tipton, and “Klansmen from Kokomo, Elwood and other cities” would assist with the ceremony, likely an initiation. The Call-Leader wondered aloud, “Who are the members of the Ku Klux Klan in Elwood?” Signs with the letters “K. K. K.” were crudely painted on brown paper and posted on homes and businesses there. By the end of November, a large crowd—some said thousands—gathered in a field on the south side of town to initiate new members. A searchlight mounted on a pole swept the perimeter to keep out unwanted visitors. On Saturday, December 9, a crowd braved the cold to watch 300 Klansmen parade in Elwood. They were led by several on horseback while a band played “Onward Christian Soldier.” Most were said to be from Tipton, Anderson and Muncie.

The Klan had come a long way by Christmas, when the Daily Tribune in Tipton published “A Klan Viewpoint” by Dr. Caleb A. Ridley. Basically the same defense of the Klan that you would hear at any of their events, the article criticized the concept of the “melting pot” before launching into attacks on immigrants, Jews and Catholics, containing slurs and lies that do not need to be repeated here.

Since sometime during the spring of 1922, Hignett had been in Anderson, making trips to towns as far as Columbus, south of Indianapolis, all plausibly giving talks to community groups, the American Legion and others. Later he was known to be in Elwood, where he was identified as the Klan organizer. On February 27, 1923, “Sergeant Hignett, of Elwood” presided at an initiation ceremony for seven candidates held at First Christian Church. The Rev. Harry H. Wagner, the pastor, said a prayer. The audience filled the church and the vestibule and many others were unable to get in. Hignett gave the standard “principles and purposes” speech introducing the Klan that went on for an hour.

The initiation at First Christian Church of Elwood was certainly not Hignett’s first as an Indiana kleagle. However, it may have been his last initiation there. In early March, Hignett disappeared from Elwood, from Tipton and from Anderson. He didn’t return to Hamilton, Ohio, but instead turned up in London, Ontario. Upon arrival there, Hignett contacted the newspapers and claimed to be organizing the Klan in that country. More likely he was fleeing obligations. According to Merrill Jones’ 1953 thesis on the Elwood Klan, it went like this:

“The Klan had been organized in Elwood scarcely six months when the local Kleagle, Irwin R. Hignett, became involved in financial difficulties of questionable character. The state Kleagle was obligated to make good a considerable amount of money. Hignett went to London, Ontario, where he made public the secrets of the Klan in a series of newspaper articles. He was a man of shady character. One informant helped the woman who was living with Hignett to pack and leave town. That informant recalled that the woman had eighteen pairs of shoes and an expensive, luxurious wardrobe. The Kleagle was the envy of other Klansmen, as several men in the White City Klan No. 19 coveted his lucrative position.”

Based on several newspaper accounts of what happened, we know Hignett wrote a bad check for $170 and that the amount was covered by Klansmen who were reimbursed by the Klan state office. The “state Kleagle” was King Kleagle D.C. Stephenson and he would have been only a few months in power.

In an interview in the London Evening Free Press, published on March 13, Hignett said he was there to organize the Klan in Canada, but this is not credible. Given what we know about his standing back in Indiana, where he had been relieved of his kleagle duties, it is very unlikely he would have been given a similar responsibility in Canada. Perhaps for that reason, that first interview to make it to print gave his name as William Higgett, from Hapeville, Georgia, a former “grand serpent” of the Ku Klux Klan. Other accounts described him as a “former grand superintendent” of the Klan from Georgia.

In that initial interview, Higgett proposed what amounts to a foreign policy of the Ku Klux Klan: a continental alliance of Anglo Saxons from Panama to Canada “welded into the greatest empire in history.” He said some other wild things, like how “future operations of the order in the United States and Canada will be along the lines of the Fascist discipline. We reorganized the klan on the old line: hooded men and shrouded horses, but we are powerful enough now to come out into the open.” Hignett suggested that the Klan would dispense with hoods, except in areas where the units must focus on “the superstitions of the ignorant.” He also said that their enemies (described as bigots and fanatics) “will be given the Fascisti castor oil treatment or something just as effective. On the other hand, the polluted filth in the Hearst type of newspapers, moving pictures and theaters will be absolutely cleaned up.” When asked how the organizing was going, Higgett said “Not so bad,” but perhaps recognizing that he’d not really done anything yet, wryly said “but I will have to return later to get the movement under way.”

Reports of William Higgett said he was “touring Canada as a rest cure” for nerves. It’s not clear why he would have contacted the media in Ontario while apparently on the run from his debts in Indiana, though it is possible he was aware that a series of burnings of Roman Catholic Churches in Quebec, which some attributed to the Klan, had inspired fear and anxiety that the Klan was organizing in Canada. So, whatever his actual involvement, Hignett stepped into the role as the celebrated “first” Klan organizer to arrive in Canada. As stories based upon his initial contact with newspapers in London went out over the Canadian wires, the rogue kleagle’s introduction of the Klan to Canadians likely caught Klan leadership by surprise.

The backlash in Canada was swift. The absurd rantings of William Higgett were followed by the intense denunciations of the Klan by Canadian law enforcement, who assured the public that the Klan would not be allowed in Canada. Possibly to explain himself, and as a form of damage control now that stories based on what he told the Evening Free Press in London had gone viral, he wrote complaining about fabrications that had been published.

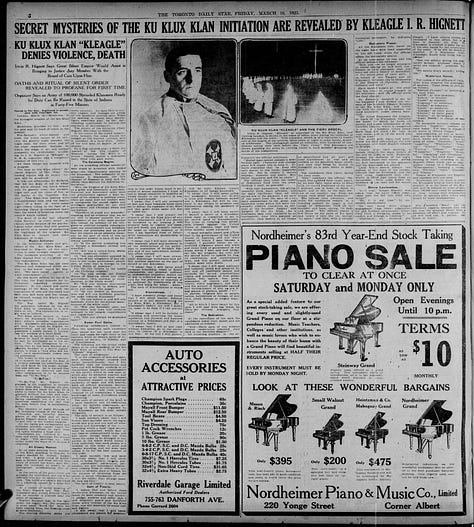

Barely a day later, as Hignett was reportedly on his way out of Canada to meet with Klan officials in Buffalo, the first of a three-part series on the Klan was published in The Star newspaper and by syndication as far as Vancouver. Hignett had supplied the the newspaper with his kleagle commission papers from Atlanta, multiple photographs and a variety of documents, including oaths and other Klan secrets. The articles, based on interviews with Hignett, turned out to be the first Canadian primer on the Klan and should be included in any anthology of revelatory Klan exposés from the 1920s.

In the Star series, Canadian readers were introduced to Irwin Hignett, an American citizen who enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces, 13th Highlanders, and then was injured, landing in Halifax, as reported here. But in the Star version, Hignett returns to Boston after the war and immediately joins the American Legion upon its formation in 1918, lecturing on its behalf before joining the Chautauqua circuit. It was through his talks on Americanization that he was approached on the streets of Anderson by a friend who asked “What would you think of an organization that lives for just these things about which you lecture?” and handed him a card which asked some basic questions about faith, patriotism, and white supremacy and which contained an invitation to Klan meeting in Anderson.

The Star related Hignett’s story of his first meeting with a Klan recruiter, a mysterious “Ti-Bo-Tim” who interviewed him before taking his money as a prospective citizen of the invisible empire. It was one year ago, the Star reported, that he was initiated into the order, his reputation as a public speaker winning him a commission as a kleagle. He claimed he gave speeches five nights a week, admitting an unknown number of men into the organization. Likely referring to Elwood, he said this included “1,600 men in eighteen weeks in one town of Indiana.”

Other than Hignett’s penchant for stretching and bending the truth, there is no reason to doubt the Star’s account of how he joined the Klan. It seemed unlikely that Hignett would have joined any later than Spring or Summer 1922, just practically speaking given what is known about his tenure as Kleagle of the Elwood Klan. And what is known about Klan nascent organizing in Ohio and Indiana makes it hard to imagine that he could have been involved much earlier. In any event, the key to this part of the Star story is that he has come to Canada to recover from the stress of facing opponents before Klannish hegemony took root in Indiana:

“Facing, night after night, a public audience containing many persons of unfriendly opinions, has worn Hignett’s nerves to a shred. All this summer he plans to rest, and then intends to organize another state.

“All this information was drawn from Hignett with difficulty. He did not relish describing personal experiences, but he talked with enthusiasm when the Klan itself was under discussion.”

The rest of the Star series tells the story of the Klan, including the first night with Col. Simmons and his crew that night on Stone Mountain. In many ways, the articles in the series offer the same Atlanta-approved talking points as a basic Klan “principles and purposes” speech, with basic apologetics for hatred and division, explaining why white Protestants need their own group even though they are not “anti” anyone, and so forth. There is the typical awkward defensiveness about the history of violence associated with the order. For example, despite a focus on law and order, Hignett follows his superiors in denying the veracity of reports of Klan involvement in grisly murders in Mer Rouge, Louisiana.

But what Hignett told the Star was not vetted by anyone and some topics would have had Klan leaders cringing, such as his revealing Klan’s political methodology in recent wins in Indiana. He also revealed some of their secrets, oaths and other proprietary information of a group that put so much emphasis on secrecy.

The Klan did not dispute the veracity of what “the first” Klan organizer in Canada told the Canadian papers. Hignett was said to have been “recalled” to Atlanta to talk it over with leadership and an agent of the order appeared in London looking for him. That man was a kleagle from North Dakota named Jack Dacotah Thompson. Thompson had worked organizing Minneapolis before moving east, first to Columbus before showing up in New York to bring Hignett for talks with Klan leadership. Thompson, a veteran who got his start in scouting and civilian officer training in the build-up to the war, later had charge of a CCC camp in Pennsylvania during the 30s and was involved in the upgrading of the base at Pine Camp, New York, to what is now known as Fort Drum.

Newspapers described Thompson as there to “arrest” Hignett and take him to Atlanta, something both men denied when Thompson eventually found Hignett in Kingston, Ontario. Hignett left with Thompson voluntarily, though it’s not clear whether they went to Atlanta, Buffalo, or somewhere else. On March 28, the Call-Leader in Elwood reported that Hignett had returned to Elwood to settle his debts, “having dropped into the city again last night and it is said that his return was voluntary and that he came to reimburse persons to whom he was indebted.”

For a few weeks, and even into the summer, Hignett’s brief romp into Ontario resounded across Canadian provinces and the American west, replaying in syndication as late as July and causing some grief that maybe William Higgett had accomplished something in western cities, if he visited them at all. Hignett, however, seems to have returned to New York, as he appears at Klan events in New York in the latter part of the year. Laurel, after all, still lived there. But it is unknown what he did or where he went. When he resurfaced he began appearing under the name “Human Dynamo,” his identity kept from the public.

When he attended a meeting of Richmond Hill No. 30, the Friendly Sons of America, in December 1923, Hignett had been busy speaking for the Klan in Nassau and Suffolk counties. Charles Wagner in the meeting minutes noted that Hignett was the “national lecturer” by then popularly known as the “Human Dynamo.” Given a few minutes to address the klavern, Hignett spoke “energetically” about how they should not focus on “small petty things” and instead work towards the “big and main things.” The next night he spoke at First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, Queens. His inflammatory comments about Governor Al Smith and Catholics in general were widely reported.

Hignett remained a figure in Queens and Long Island during the first weeks of 1924, making several appearances there and in the Southern Tier and Western New York, especially Wyoming County where he spoke in several towns, including Bliss, Warsaw, and Perry, where resistance by townspeople forced Hignett and the Klan to switch venues. At a recruiting meeting in Waverly, near Binghamton, about 200 Klan opponents circled the building and then attacked the 100 or so who had attended the meeting. A melee ensued and Hignett was beaten severely, with further injury to his arm. A mention of this was made in Richmond Hill.

In January and February 1925, he underwent surgery on that arm, the twenty-seventh operation to address wartime injuries, he told the Ithaca Journal. Despite the attempts made to reconstruct his elbow using metal plates, at some point his arm was amputated at the elbow. Newspapers noted that his surgery was paid for by the Canadian government with cooperation from the U.S. Veterans Bureau.

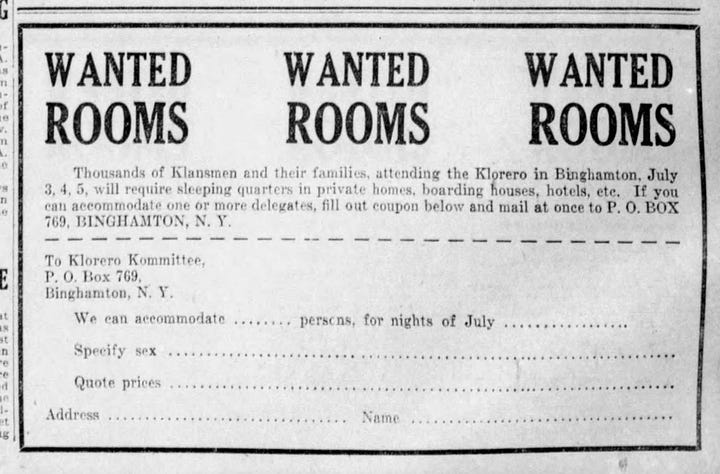

An address scribbled on Hignett’s Canadian service records from this period turns out to reveal more than first thought: PO Box 769, Binghamton, New York, this address replaces the previous one in his service record dating from his time in Halifax. The date of this annotation was simple to identify when a search showed that the post office box was controlled by the Klan at the time and was circulated publicly in the run-up to the Klorero (state convention) held in Binghamton that summer. The advertisement from the Press and Sun Bulletin in Binghamton provides a somewhat curious insight into the culture of the Klan community.

Irwin Hignett was in good enough standing with the Klan—and its King Kleagle Maj. E. D. Smith—to have important correspondence from Canada sent to the Klan mailbox in Binghamton. Hignett remained very busy for the next year, appearing more often as “Rev. Irwin Hignett” than “Human Dynamo.” He continued to speak throughout New York State, from Long Island to the Southern Tier, occasionally appearing in the paper for his work with the Klan.

One question that remains unresolved is how Hignett managed to get out of his scrape with the Klan, owing money in Indiana, then skipping out and making a splash in the Canadian newspapers—only to return and resume public speaking for the Klan, seemingly in their good graces. It may never be known how much his reputation as the dynamic “Human Dynamo” helped, if he had any remaining charisma, or if it was enduring friendships with E. D. Smith or other Klan leaders that paved the way for his continued prominence as a “national lecturer” for the Ku Klux Klan.

Barely into his 30s, Hignett continued his shady ways. At the end of 1925, he was arrested in Montreal for skipping out on a hotel bill. Newspapers described him as from London, Detroit, and Toronto. He was held three days and released after paying the debt. According to one account, he had held two meetings within a week but promised the court he would leave Montreal for Toronto. It is not clear if this incident brought his association with the Klan to an end, or if it just became more obscure.

Hignett next appears in Los Angeles in 1927, when he married Ruth Lorraine Ferree. They lived in Fresno, where Irwin opened a silk hosiery business with an office in the Rowell Building. A few years later, Ruth Hignett sued Anita D. Roth, a wealthy San Francisco property owner and landlord in Pacific Heights, for “alienation of affection”—for stealing her man. Roth and Hignett insisted they were just friends and the suit was tossed on a technicality when Irwin said he had already separated from Ruth. She divorced him soon after. Not including his 1930 census form, which shows him living in Beverly Hills, there are traces of Hignett in Fresno, Pasadena and Santa Barbara, where he opened a garden supply store, is involved in the local chamber of commerce as well as organizations, such as the Optimist Club. In 1935, he filed for divorce from Laurel, who in 1940 listed herself as still married; she was described as widowed in the Rochester city directory. She died in 1948.

In 1936, Irwin is a “San Jose salesman” when he is arrested for writing a series of worthless checks while on a trip down the coast with two women, one of them he intended to marry. Although information is scarce, he served time, after which he appeared in Vancouver, British Columbia, where he launched a new life, marrying Phyllis Adelaide Read in 1938. Over the next few years they had two children. He maintained his affiliation with the Optimists and other social service and veterans organizations. The family spent some years in Edmonton, where for a time he was the manager of the classified advertising section of the Edmonton Bulletin, but they returned to Vancouver where he was active coaching and organizing youth sports and was seen as a champion of youth sports in Vancouver when he died in 1954. Phyllis took out a brief classified ad a few weeks after he died, thanking everyone for the outpouring of support as she grieved the loss of her “beloved husband.”

Before you laugh, or shake your head, a coda, perhaps.

In the introduction to his book, Citizen Klansman, on the rise and fall of the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, Leonard Moore cautions against assuming that this “huckster” nature of the kleagles means that members were “beguiled” or were somehow without blame. The Klan was not an aberration; it arose only because the communities accepted it and conversed with it. Where they did not, it quickly withered.