Late on a Saturday night in a smoky and cramped lodge meeting room of the Richmond Hill Masonic Temple on 114th Street, one man dressed in a burgundy Ku Klux Klan robe stands next to an altar and in front of a group of other men. Mostly hidden by shadows, they appear to be in their 20s and 30s, with angular jawlines and razor-sharp hair. Electric lightbulbs mounted in a cross hum incandescent in the corner. The man in front makes a series of statements, like a prayer but without the content of a prayer. Turning to a flag mounted near the corner, and concluding the meeting's opening exercises, the men join in singing “Star Spangled Banner.” A wider view shows a few simple holiday decorations.

After the minutes of the previous meeting were “approved with a few corrections,” #99—as they were identified by number only in those early days—made a motion that “a bouquet be presented to Mr. Jones of Inwood No. 3 not costing less than $2.” Subsequent meetings reveal that Mr. Jones was in the hospital for a spell but returned home before the end of the year. Seconded by #5, the motion carried. Visiting the meeting that night were Klansmen James Rozell from Baldwin in Nassau County and Richmond Hill resident Charles Hewlett from Jamaica No. 5.

We don’t know what happened at that previous meeting or how many previous meetings there might have been, because no meeting minutes from this group survive before December 8, 1923. Whatever happened before December 8, when they started meeting or who the original organizers were, we will never know. For that, we have only clues, each a single piece from a giant puzzle presented as if in a darkened room. But once your eyes adjust, and you stare at it long enough, a single puzzle piece can be quite informative. Add some other pieces and a story emerges, however fragmentary it may appear at first.

Apparently, there had been a special committee dedicated to organizing the unit and writing bylaws. #20 was a member, we know, because in that capacity he nominated #262 to serve as kligrapp (secretary) of the organization. This was seconded by #190 and approved. Empowered by this action, #262, Charles M. Wagner of Parkview Avenue in Glendale (that’s 80th Street today), began recording the minutes, launching what would be at least a decade of service to the organization, known in December 1923 as Richmond Hill No. 30, Friendly Sons of America, a provisional unit of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Much of what we know about Kligrapp Wagner can be told fairly quickly. We know that he first paid his dues in late September, one of thousands on Long Island that fall who attended dramatic meetings with fiery speeches under burning crosses. Through a little online sleuthing, we find a bit more about Charles Wagner. One of several brothers to join the Klan, Wagner came from a family in Bushwick active in the Junior Order of United American Mechanics (JOUAM), a little-remembered society in a tradition of nativist intolerance that includes the Know-Nothings, the American Protective Association and others that would be denounced today for their hate-fueled exclusionary politics. The Wagners were so well known in the JOUAM circle that the “five Wagner brothers” were notable escorts of the JOUAM State Councilor Raymond D. Gurnee, later mayor of South Nyack, when he paid a visit to the Nathan Hale Council at Triangle Hall at Broadway and Halsey. In 1916, Charles and brother James marched in the inaugural Fourth Ward Memorial Day Parade as officers of the United Boys’ Brigade. In the years before that, he had been a member of K.U.V. Bavaria No. 1 in Bushwick, a mutual aid society that provided insurance-type support for German families. Such mutual aid was a feature of many benevolent societies, and even malevolent ones like the Klan had an insurance program as one of its subsidiary businesses.

While some radical Protestants were dour and self-serious, Charles Wagner was a cornettist who enjoyed drama, and he participated in dramatic productions well beyond his school and church club years, including with the Richmond Hill Klan. In addition to family weddings and a variety of other gatherings, the Wagners threw at least one Halloween party at their home on Parkview Avenue less than a block north of Forest Park. The party was written up in the Chat, and the description suggests they were a fun-loving people.

“Upon arriving the guests were met at the door by the “devil,” who escorted them to the ghosts which grew in numbers as the evening progressed. The rooms were artistically decorated with the Hallowe’en colors, autumn leaves, black cats, witches and lighted pumpkins. A huge spider web covered the ceiling of the dining-room.

“At the conclusion of the festivities the guests were led to the dining-room where they were greeting by an elaborately decorated table decked with goodies of every description. Much merriment ensued when they partook of several large cakes, in the depths of which were hidden all sorts of tiny souvenirs.”

While all of the Wagner brothers joined the Klan, it appears only James and Charles were active as officers of local units in Queens. In 1946, New York Attorney General Nathaniel Goldstein named James Wagner as having been a county leader, possibly an exaggeration of his role, but the fact that AG Goldstein’s report, which included a list of more than 1000 members, does not survive in state archives nor in national repositories makes follow-up nearly impossible.

Of those thousands of men who became members in Queens, little is known about most of them. The inclusion of the names of visitors to the December 8 meeting offers some insight into the workings of the Klan more broadly. Wagner does not associate Rozell from Baldwin with a particular unit. The Nassau County organizations to which he would have belonged were coming together at the same time as Richmond Hill No. 30 and Jamaica No. 5. That a member of the Klan would attend a meeting of the newly formed Richmond Hill No. 30 is another piece of the puzzle. It suggests something about the level of development of the organization on Long Island. What it means exactly we’ll have to talk about later.

With a little work it’s easy to find that, like many Klansmen in central Queens, Charles Hewlett from Jamaica No. 5 worked on the railroad. In 1920 he told the census taker that he worked for the Long Island Rail Road as an engineer. A few more clicks and we find that Hewlett died in 1950 at the age of 83, his wife Sarah passing the following year. At 55, Hewlett was one of the older men in the room that night in December 1923. Earlier in the year, his 32 year old son Harry, a mechanic who at times also worked on the railroads and lived with his parents on 111th Street in Richmond Hill, died of accidental gas asphyxiation in the bathroom while reading a book. Like his mother, Charles Hewlett was born in the West Indies, which is notable because membership in the Ku Klux Klan was reserved for those born in the United States. It’s possible he lied about his birth to the Klan but not the government.

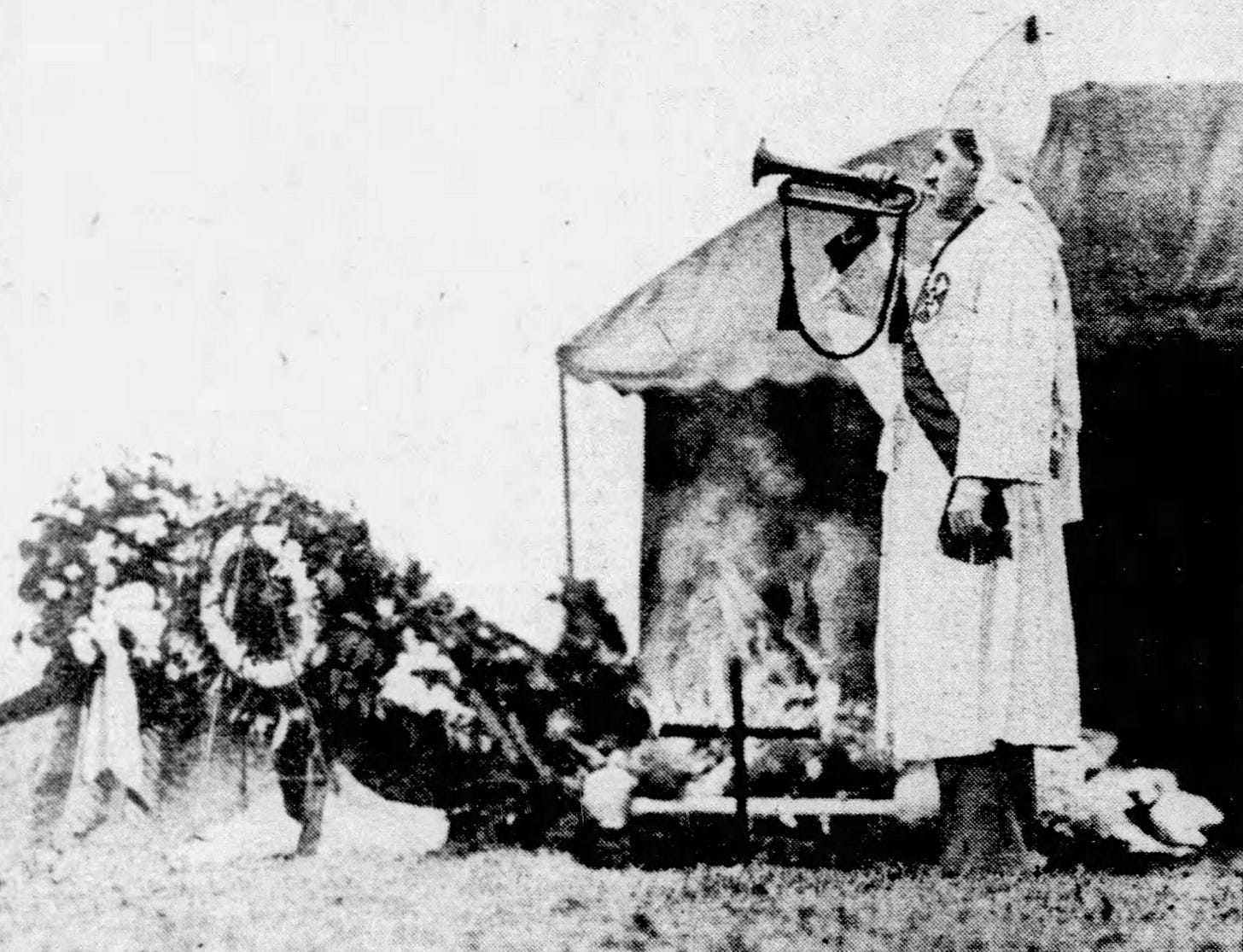

What were Hewlett and Rozell doing at the Klan meeting? Each mark on paper in the archive offers another clue, though some take a while to decipher. In future months, Klan officials from local, state and national Klan officers would visit the Richmond Hill klavern. Seeing that James Rozell visited the Klan in Richmond Hill on December 8, as he did again a week later, is confusing initially because another Rozell family, possibly a distant relation, was active in the Klan in Queens, including another James Rozell. J. B. Rozell from Baldwin also worked on the railroad, that is, until he was crushed to death between two cars in Brooklyn’s Flatbush Yards in 1929. Although we know little of his Klan membership, we know that James B. Rozell was given a Klan funeral, an image of which was printed in the newspapers. By the end of the decade, another of the Queens Rozells would become Exalted Cyclops, or local leader, of the Jamaica Klan No. 38. But first things first.

With its clues and random puzzle pieces, the regular Saturday night meeting on December 8 was anything but dramatic. The men of Richmond Hill No. 30 conducted the routine business a relatively new organization. Because Christmas was in the air, arriving as the nascent organization was bursting with membership applications, at meetings on December 8, 15 and 22, they discussed their charity work, including the plan to purchase gloves for the children of the Ottilie Orphan Asylum in Jamaica, a favorite cause. Over the next years, the men of the Richmond Hill Klan would often take the orphans for auto rides or to the beach in Bayside. Once, the “Boys Band” of the Ottilie Home marched with them in a parade in Great Neck, though it is not clear whether the men dressed in regalia or not. To keep their generosity in perspective, please remember that at times they sent money to the families of crime victims—notably when the perpetrator was not white.

As Christmas approached, New York newspapers from Montauk to Niagara Falls published frightening stories of Klan meetings, burning crosses, and threats to public order amidst racial and religious intolerance and xenophobia. The new Klan unit was born into raging conflict—it had been a busy if chaotic year for the Friendly Sons of America. In April, the first of them paid their ten dollars and took an oath to the Klan. Twenty-five or so signed up in May, then more than fifty a month did in June, July and August. Nearly double that were initiated in September, October, and November, so many in fact that by December most of the men who were then members had joined after Labor Day at a series of spectacular meetings in Huntington, Wantagh, Babylon, Bay Shore, Freeport, and Oceanside.

In the meeting, the tone was more business-like. An invoice for robes was referred to the finance committee, so we know there was one of those before this December meeting. A treasurer’s report showed a few disbursements; it also showed that December 1 dues brought in $34.50, and a little more than that was added to the relief fund. A motion was made to use money in the automobile fund, about fifty dollars, for the Christmas fund, something that was seconded and approved. #235 proposed a Christmas committee “to expend the money appropriated” and then report back on how it was spent. This too was seconded and approved.

The Friendly Sons also heard from the Exalted Cyclops, who was unidentified even by a number. In a kind of chairman’s report, he covered a range of issues, often relaying messages from superiors in the national or state leadership. The EC discussed the Christmas fund and how the office would only be open on Tuesdays and Thursdays after the coming week. It’s unknown where their office was located, but very likely it was in the same Masonic Temple where they met. In a couple of years, they would rent a storefront on Jamaica Avenue in Jamaica, and they did come to hold meetings there, but in 1923 organizational resources and people were still arriving from the South. According to the EC, the new women’s organization was going to be led in New York by Mrs. Goodwin. If you follow the emergence of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan (WKKK), this is a small but significant piece of the puzzle. (And as a brief aside to that, I spent a few days on and then cut a thousand words about Mrs. Goodwin, who deserves her own post.)

James Rozell from Baldwin then spoke about Sunday services at the Baldwin M.P. Church, asking to have a delegation from the Richmond Hill unit appear in regalia. To this end, #147 was asked by the EC to organize volunteers. There would be no shortage of men willing; the visit to Baldwin, at a time of rising tension over the Klan’s expansion in New York, would prove consequential. The EC thanked two other men for their service as interim co-treasurers.

Evidence shows that by December 1923, whatever organizational infrastructure was in place in the Richmond Hill Klan No. 30, they were still undertaking basic organization work, such as crafting bylaws and forming committees. At the December 8 meeting, they created an executive “committee of 3” to open a bank account at the First National Bank of Jamaica. This had been proposed by #20—Charles Aff—and #11, #47, and #9 were nominated. When no one else was put forward, Aff closed nominations and the three were elected by acclamation when Wagner cast a single ballot. Aff and others discussed the nature and structure of the executive committee and advanced a motion proposing that it have a president, vice president, and treasurer, that they identify a substitute, and that all of this information be shared with the bank as well. After #14 seconded the motion, it passed.

After a recess, Wagner recorded in the minutes that “#15 made a motion to appoint a committee to take care of various affairs, open air ceremonies, church affairs, etc.” Seconded by #5, it passed. A cross burning in St. Albans less than two weeks later suggests they wasted no time with that. Of course, they had already been visiting churches.

Just the weekend before, on Sunday, December 2, a delegation of a dozen or so men from the Friendly Sons of America paid a visit in robes to Hillside Presbyterian Church in Jamaica. We know they did because it was reported in the newspapers. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle said that 25 Klansmen were there, and the Long Island Daily Press reported that 16 Klansmen “broke into the church” during the sermon, the title of which was “Why the Decline in the Life of the Church?” They silently marched down the aisle to the pulpit where they presented the pastor, Rev. Dr. Joseph MacInnes, with a miniature Klan hood and seventy dollars cash. One of them asked permission to address the congregation as to the nature and purpose of their order and MacInnes allowed it. Because of this spectacle and the attendant crowds that came every time the Klan made an appearance like that, according to the Daily Eagle, “more than a hundred persons were unable to gain admission” to the evening service. Not a bad way for a church in decline to end a day that began at 9 am with Sunday school for children and Bible study for adults.

Angered by how the Long Island Daily Press of Jamaica got mixed up about what was going on, Rev. MacInnes called the newspapers. “They got it dead wrong,” he told the Daily Eagle. “They didn’t break into the service because I knew they were coming.”

“Last week, the pastor explained, “a member of my congregation who is also a member of the Klan wanted to know if I would like to have some prominent Klan members come before the congregation and explain what the Klan stood for. I said ‘Yes, bring them along.’ It was understood that when the male quartet sang ‘Cling to the Saviour, My Boy,’ the Klan members were to file in and speak.

“Twelve of the leading Klansmen came in,” he continued. “They wore white robes but they were unmasked. They had hoods, but the hoods were thrown back so that the faces were visible. The only reason why they wear masks is because when a man happens to become a member of the order and becomes a traitor he can’t tell who initiates him. And they wear their robes just as I, a chaplain of the Masons, have a uniform I wear.”

“One of the leaders asked me if he could address the meeting and define the tenets of the Klan, and I told him yes. I was very glad to have the order explained last night. I’m patriotic and I wouldn’t stand for anything in my church that isn’t patriotic.”

Rev. MacInnes was also quoted repeating a claim they made often, that the Klan doesn’t stand for violence and is all about law enforcement. Klansmen take an oath to refrain from violence, he claimed, and are only against Catholics because Catholics are trying to assert control over the government. “They are not against anybody,” he said, referring to the Klan. They just are opposed to the mingling of the races. MacInnes claimed that the Klan was not opposed to Jews. However, he asked pointedly, if “the Jew wouldn’t let you into his orders. Why should he be admitted to ours? They are against the Jew only where the Jew shows himself to be an enemy to the traditions our ancestors fought for.” To top it off, MacInnes denied that the Klan burned crosses, suggesting it was the work of their enemies. He gave the maligning newspaper 48 hours to rescind its story that the Klan visitors were unwelcome guests that night. He also denied he was a member.

The paper that supposedly got it all wrong, the Long Island Daily Press of Jamaica, in its follow-up described a “cheery” MacInnes phone call asking for the “religious editor.” The editor himself took a friendly tone, reporting that he replied to the caller that he wasn’t sure he was religious, but was in fact the editor the caller was seeking. MacInnes again complained about the Daily Press claiming the Klan were uninvited. The idea that a church would offer them a platform was apparently as hard to grasp then as it is now. He told his story to the Daily Press which printed what he said:

“The men were there all through the service. Near its close they went downstairs and put on their robes. Then they marched in in dignified, orderly fashion and with all propriety and respect asked for permission to be heard.

“They were not masked.

“So I do wish, Brother, that you would correct the wrong impression that has gone out concerning these Klansmen, and let it be known that all they did was in the most proper and orderly way. Thank you, Brother.”

According to the Daily Press, speaking to the Klansmen after receiving their gifts, Rev. MacInnes,

“... replied that the hope of the Klan lay in the way they live their lives, and reminded the Klansmen and his congregation that the disciples of Jesus Christ were abused and misunderstood; but today their work and faithfulness to duty is bearing fruit.”

Despite denying that he was a member, #430 Rev. Dr. Joseph MacInnes was initiated into the Ku Klux Klan on November 15 and wasted no time inviting the Friendly Sons to visit his church on Jamaica Avenue at Harvard Street, what is now known as 177th Street. After the hubbub bubbled up into the papers, the trustees of Hillside Presbyterian met to discuss the situation and afterward affirmed their support for their pastor, denying that any criticism of him was considered. The unnamed trustee quoted in the Daily Eagle story said it was not their business in any case, since it was a matter belonging to the Board of Elders, who could consider it at their next meeting. After that Wednesday the incident was not mentioned again in the papers. One possible reason why was left unstated at the end of the interview with the unnamed trustee: “Asked if any of the trustees were members of the Klan, he answered: ‘I don’t know.’”

In the newspapers at least, and beyond the story of the visit to his church, there is no evidence that MacInnes was involved in the Ku Klux Klan. Hillside Presbyterian Church was advertised alongside other Jamaica churches in the Daily Press. In all published accounts of him his was a typical ministry. Typical of many New Yorkers, he vacationed with his wife Mary (Stuart) in West Falmouth, Massachusetts, and upstate.

But Rev. MacInnes was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. His name and information appear on an index card used for maintaining the membership rolls. Not only that, but as part of its application for a charter from Atlanta, in January 1924 there was an outside audit of the Richmond Hill Klan’s books listing all current membership, the dates they joined, how much they should have paid and how much they actually paid. MacInnes is listed as in good standing in January 1924.

Rev. Joseph MacInnes was one of the more visible community leaders in Jamaica who could be relied upon to participate in such Klannishness as was the case. As a Protestant pastor at a meeting of radical Protestant men, MacInnes occupied a position of reverence and authority. He spoke at meetings and when he did not speak he was often spoken of. The Exalted Cyclops encouraged the brothers of the lodge to attend Reverend Mac’s gatherings, or his church, and they did. When he got sick they were asked to visit Mac at his bedside.

Rev. Joseph MacInnes was born in 1870 in the old ninth ward of Manhattan, what is considered now the West Village, the youngest son of John and Margaret, both originally from Scotland. His mother passed away when he was just about a year old; his father died when Joseph was 14.

He had two older brothers, William and James. James entered the publishing industry at 17 after a public school education. After a quick rise in the ’90s to some level of distinction as a man of letters, an agent and publisher, James moved to Brooklyn where he was elected alderman of the eighteenth assembly district. A member of the minority party in an age of Tammany dominance, he was the leader of the Brooklyn Republicans when he lost the election for President of the Board of Alderman in 1900; he was elected to Vice President of the Board that year and served under the Mayors Van Wyck and Low. Highly regarded during his multiple terms as a defender of Brooklyn and a fighter for the wards he represented, he lost the nomination to a candidate who had worked for Inter-State Paving Company, which had contracts in Brooklyn at a time when such contracts were rife with corruption. James Hamilton McInnes died in 1922 while vacationing with his family in Trumansburg, NY.

In the family plot in Maple Grove Cemetery in Kew Gardens, Queens, the names are all spelled McInnes. While usage is mixed in reports of Rev. Joseph, it becomes uniformly MacInnes after about 1909. There is no explanation for the alternate spelling used by Joseph, even in church advertisements, but it may have been to distinguish himself from his relatively well-known brother.

Not much is known of Joseph MacInnes before the turn of the century. He most likely attended public school, like James. The Brooklyn Standard Union after he died claimed he graduated from Union Theological Seminary, but there is no evidence of that in their alumni directory. The U.S. Census reveals that in 1900 an unmarried Reverend Joseph McInnes was a lodger at 350 West 35th Street in the home of Andrew Coyle, a widower who worked as a maker of shoe lasts, and his two adult children.

At least one source has it that he had an appointment at Tuckahoe in Westchester County, before being called to the pulpit of the Bensonhurst Presbyterian Church in December 1905. However, the Brooklyn Times included in the announcement of his installation at Bensonhurst Presbyterian that “Dr. McInnes comes from the Manhattan Presbytery, where he has had a long and successful ministry.”

It can be said that his days at Bensonhurst were active and largely successful. Among the services and programs, at least one meeting of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union was held at Bensonhurst Presbyterian during his time there. Mrs. MacInnes was active in the church community, participating in social events as might be expected of a pastor’s wife. After only four years, in October 1909, Rev. MacInnes was called to pastor in Unionville, NY, near Middletown. In both places his preaching was described as “earnest” or “attractive.”

At a meeting of the Hudson Presbytery in 1917, MacInnes was elected to attend the synod at Watertown in October of that year. In February 1918, he was installed at Hillside Presbyterian Church. It was known within Presbyterian circles that he was a successful pastor, and even as he spent Saturday evenings meeting with the Ku Klux Klan, Hillside Presbyterian was in the best shape in its near 20 year history: contributions were up and membership growing. After the mortgage was paid, the celebratory “burning of the note” was described in the paper.

For many years, Rev. MacInnnes was involved in Christian Endeavor, an evangelical youth society he said was “the best place to seek friends, the school to learn how to pray in public and the place to look for inspiration.” CE was a popular movement at the time, providing social events in the context of work for Christ, and it was likely a source of potential members. Research suggests that participation in Christian Endeavor was common among some Klan members and many ministers associated with the Klan. This is not to suggest that CE endorsed the Klan, though clearly some associated with the movement did.

Like many of the other members of Richmond Hill Klan, Rev. MacInnes was friendly with the Ottilie home for orphans and its leader Rev. George Godduhn. Rev. MacInnes invited the Ottilie Home children to perform a musical program at a “Children’s Day” event at Hillside Presbyterian Church. It was said he led a robust choir.

We know that MacInnes remained with the Klan through his time in Jamaica. He left Hillside Presbyterian Church in 1926, taking a position at Pleasant Valley near Poughkeepsie. It was said in the Chat that his congregation was surprised when he submitted his resignation in September. He was “greatly beloved” by those who worshipped there.

In a 1928 article about the GAR Memorial Day services, he is described as living in Pleasant Valley near Poughkeepsie. In his speech that day he epitomized the concerns of many in Protestant America:

“When I see that red in the flag [...] it seems to say to me: ‘MacInnes, all that you enjoy—all that you ever hope to enjoy—is the outcome of what these brave men sacrificed on the field of battle’ That red also stands for courage—and we need courage today, beloved. Especially do our young people need courage—moral courage—with which to face the temptations of life today. He who displays moral courage is just as much of an asset in his community as he who displays physical courage, for he stands for all that is noble, true and right. We must ring with courage to stand up for what is right, even though we stand alone. But courage and sacrifice go hand in hand.

“And when I look at the white in our flag I know that it stands for righteousness and justice and what is righteousness? It is rightness, which, as American citizens we must stand for and we must stand for purity, virtue and justice. There is much impurity in our country today. Divorces today are increasing and I say God help America when the home is destroyed.

“There is impurity in our literature which we must guard against--there is impurity in our moving pictures. Too many of us have forgotten what the white means in that flag--and we must not forget.

“Then what about justice? What about justice to each other—to all the phases of life—to other nations? We must not forget that.

“And then when I see the blue and the stars in that flag I am reminded of God’s firmament and I am reminded of God. We must not forget, beloved, that what we have achieved as a nation has been all because God was with us, acting as our leader. All that we have we must thank God for. The blue in our flag calls us to loyalty to God.

“All nations are watching us at this time, my friends and we must show them how loyal we are. We must keep that flag from stain of any kind.”

After 29 years in the ministry, Joseph MacInnes died at age 58 in October 1928 after a sudden attack of pneumonia, two years after leaving Hillside. Services were held in Jamaica, Queens. He was survived by Mary. The census in 1910 and 1920 lists no one else in the manse, and it seems all but certain they had no children.

At the December 8 meeting, the Friendly Sons resolved to reimburse the Exalted Cyclops for covering the cost of the hood presented to Rev. MacInnes at his church. When MacInnes first joined and took his obligations, the men of the Friendly Sons likely already covered his membership fee and other costs, such as for his robe and (full-size) hood. There is no proof of this, of course, and nothing about them exists before that meeting, but the Klan often incentivized ministerial support that way. Earnest believers, yes, but it was a shrewd sales tactic to cover or waive fees for membership and regalia of those Protestant ministers who joined their ranks and to give gifts of cash, even sacks of gold when visiting a church. The Friendly Sons put a hat at the door during their meetings so men could make donations to the churches the church committee resolved to visit. Those clergymen then hyped the Klan, giving talks punctuated by the fearsome spectacle of the silent procession of the Ku Klux Klan that drew large crowds to what were often modest churches.

We know that No. 30 was a provisional unit, meaning one operating without formal charter from the Atlanta headquarters of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc. This was the case throughout Long Island, where, according to the Klan in November 1923, they had 20,000 members and were adding members at 800 per week all without a single charter. Historian Wyn Craig Wade says the Klan under Simmons held up approving charter applications because doing so allowed the imperial office to reap more of the membership fees from dues-paying members. A chartered unit’s dues would be shared locally, at the state or realm level and with the national office. Under Evans, charters seem to have been granted more frequently, though sometimes with interference from the realm or national leadership. Over the next couple of months, the Friendly Sons would put together the requisite paperwork demonstrating certain benchmarks, such as a dues-paying membership of 500 and an audit of the group’s finances, but as it did so several changes were imposed from Atlanta, at a time when the acrimonious split between the old Imperial Wizard William J. Simmons and the new Imperial Wizard Hiram W. Evans, was being felt locally.

We’ll return to the interventions by national Klan leaders later, but first we have to get through December, and the events the next week in Baldwin after they visited the church.

This is fantastic. Such rich detail resulting from an obviously deep dive.

One quick thought in reaction to a detail - while incorrect, many associate Mac with Scotland/Protestantism and Mc with Ireland/Catholicism. Maybe something there, given the context and the group orientation?